– source

– source2025-01-14T16:00

Originally sketched on September 29, 2023.

I'm incredibly excited about Cubed. When I first learned about the project via this Xarray blog post, I knew it was worth betting on. To be able to perform array computation serverlessly -- without having to worry about managing memory (!!) -- seems like the future of data science in the cloud.

This slide deck from Tom White, the primary author, does an excellent job of introducing Cubed.

Maybe the primary source of my excitement was in this project's potential to change array acceleration. Today, performing computation with arrays on GPUs/TPUs is still really difficult, even with the cloud.

– source

– source

Particularly difficult, until maybe recently, is working with really, really large arrays on accelerators. For most ML projects, the standard recommendation is to put as much of the dataset in memory (i.e. RAM) in order to minimize wasted cycles traversing the memory hierarchy (both the CPU and (G/T)PU hierarchies). Most ML data pipelines (e.g. tfds) are designed to efficiently schedule resources (network, disk, RAM, CPUs, etc.) to keep GPUs saturated. ML examples are often written into protobuf (tf.records) or flatbuffers (I assume what pytorch uses?) and then efficiently loaded into memory to keep accelerator hardware as busy as possible.

This becomes much, much trickier to do when you can't dump all your tf.Examples in memory, or even on disk. This setting is common in the world of frontier LLMs, but more interesting to me, in scientific computing settings. How do you train an ML model when your dataset is over a petabyte in size (or, say, 6 PiBs)?

And if you really want a challenge, this is probably the biggest singular Zarr dataset in existence (~6PiB):

github.com/google-resea...<br><br><a href="https://bsky.app/profile/did:plc:lozmph3nfogiyoi23m4qrxus/post/3leq5wp7z622a?ref_src=embed">[image or embed]</a></p>— Al Merose (<a href="https://bsky.app/profile/did:plc:lozmph3nfogiyoi23m4qrxus?ref_src=embed">@al.merose.com</a>) <a href="https://bsky.app/profile/did:plc:lozmph3nfogiyoi23m4qrxus/post/3leq5wp7z622a?ref_src=embed">January 1, 2025 at 7:44 PM</a>

Worse still: many modern ML tasks make use of multiple datasets. Each example is commonly a windowed, jittered combination of several data sources. In the geosciences, for example, it's typical to require combinations of multi-petabyte data sources. Can you imagine pre-caching these windowed combinations as protobufs? It would literally expand the amount of data needed to be stored factorially — starting from petabytes!!

This, in a nutshell, is why work improving cloud-optimized data

loaders is so important. Imagine keeping accelerators busy while

creating ML examples just-in-time. Since streaming data into the unit of

compute is inevitable when it can only be stored in cloud buckets, data

loaders keeps accelerators saturated, navigating the memory hierarchy

for you, hopefully with a flexible interface. xbatcher,

pioneered by EarthMover and the Pangeo collective, is one such example of

this infrastructure. Maybe the one I'm most excited to use soon is this internal

data loader developed by the team who created NeuralGCM.

(I figure, the more I keep talking about it, the more likely the good

folks at Google will turn it into an open source package 😉). This is

also why, I argue, investment spent benchmarking

and optimizing the internal components of these data loaders is time

well spent.

Data loading, however, is only one part of the puzzle. Reshaping data, today, is still quite a big pain, especially for petabyte-scale inputs. Even with state-of-the-art cloud-optimized data formats, coalescing source datasets into the appropriate shape for models is data-engineering intensive. Note, for example, Keenan's experience just the other day (emphasis mine):

In my work I’m struggling with providing data from xarray to a machine learning model. I’m aware of tools like xbatcher in this blog post and this other thread. I run into two main sticking points:

- Randomly shuffling examples is very important. We get vastly different model performance depending on the order data is provided during training (see notebook).

- Constructing windowed data with xarray is very memory intensive. If I want to slice out all non-NA windows of a certain size, I have to iterate through small chunks of the data (this approach was the solution in the thread linked above).

My process now is to write an intermediate dataset for a given window size, drop NAs, shuffle, then train a model. This works, but then every time I want to modify the input data (e.g. try a 5x5 window instead of 3x3) I have to write a new intermediate dataset.

Even with elegant interfaces to express data massaging (Xarray), managing physical resources (memory, storage) takes up a significant amount of developer time during ML modeling.

Maybe you're like me, and after reading this, you find yourself thinking, "Couldn't we automate this data engineering task, especially given a sufficient Xarray-based specification for what the data should look like?" If so, then you'll likely share my excitement for Cubed, which, in my opinion, is a framework perfectly fit to address this problem!

Cubed, unlike other data engineering systems, is array-aware. Since it has been designed to respect memory constraints, it can automate rechunking ARCO datasets according to the desired output no matter how arbitrary. Internally, Cubed strategically dumps intermediary arrays as Zarr stores, as it has enough understanding of the global operation DAG and underlying compute resources (namely, RAM), it solves this game of memory whack-a-mole for you. That's the dream of Cubed, as far as I understand it.

If you'll permit me to indulge in a moment of possible science fiction: what fundamentally separates the scheduling happening on the data engineering side from the internals of the ML training or inference? From where I stand, I can't help but notice parallels between the advanced scheduling systems happening in, say, XLA or MLIR, from the scheduling happening within Cubed. If there are parallels, could we find a way to make them work together?

I think so. And, for these reasons, I am passionate about investing in finding ways to make Cubed work with accelerators.

The first milestone that I see worthwhile to pursue is to integrate Cubed with Jax. Jax, for the uninitiated, is as simple as numerical/ML libraries can get, but no simpler. This is how Jax was introduced to me:

Imagine you were tasked with designing the machine learning framework of the future. What are the fundamental components the framework should have, given that the goal is to make them run on heterogenous, accelerated hardware? Well, after careful consideration, it should do four specific things:

- It should perform automatic differentiation ("autograd").

- It should offer linear algebra primitives (like NumPy)

- It should handle randomness (since randomness on accelerators is non-trivial)

- It should come with standard crypo libraries (for security – you should never roll your own – and also because this is non-trivial on accelerators).

That's it. This, more or less, is Jax .

– Paraphrasing a talk I heard once at Google.

Jax works by providing these four essential components to Python via a Just-In-Time (JIT) compilation. What this means, more or less, is you can slap a decorator on your function of NumPy-like code, and it will turn it into well optimized MLIR/XLA IR (i.e. intermediate-representation) to run on all sorts of hardware.

(For the record, I think that PyTorch would also work well as the underlying array acceleration framework. It can do pretty much everything that I've described here. However, due to my understanding of the trajectory of PyTorch's development path, I think Jax is the better bet.)

Once this milestone is achieved, I think it will enable really interesting stuff. For example, every serverless compute provider underlying Cubed, in my understanding, offers serverless GPU support. This infrastructure is getting more popular today for ML model inference thus becoming a commodity. In practical terms, I imagine this would mean non-trivially cutting down the time to perform compute-heavy operations — the core array work would all be performed by GPUs (or TPUs).

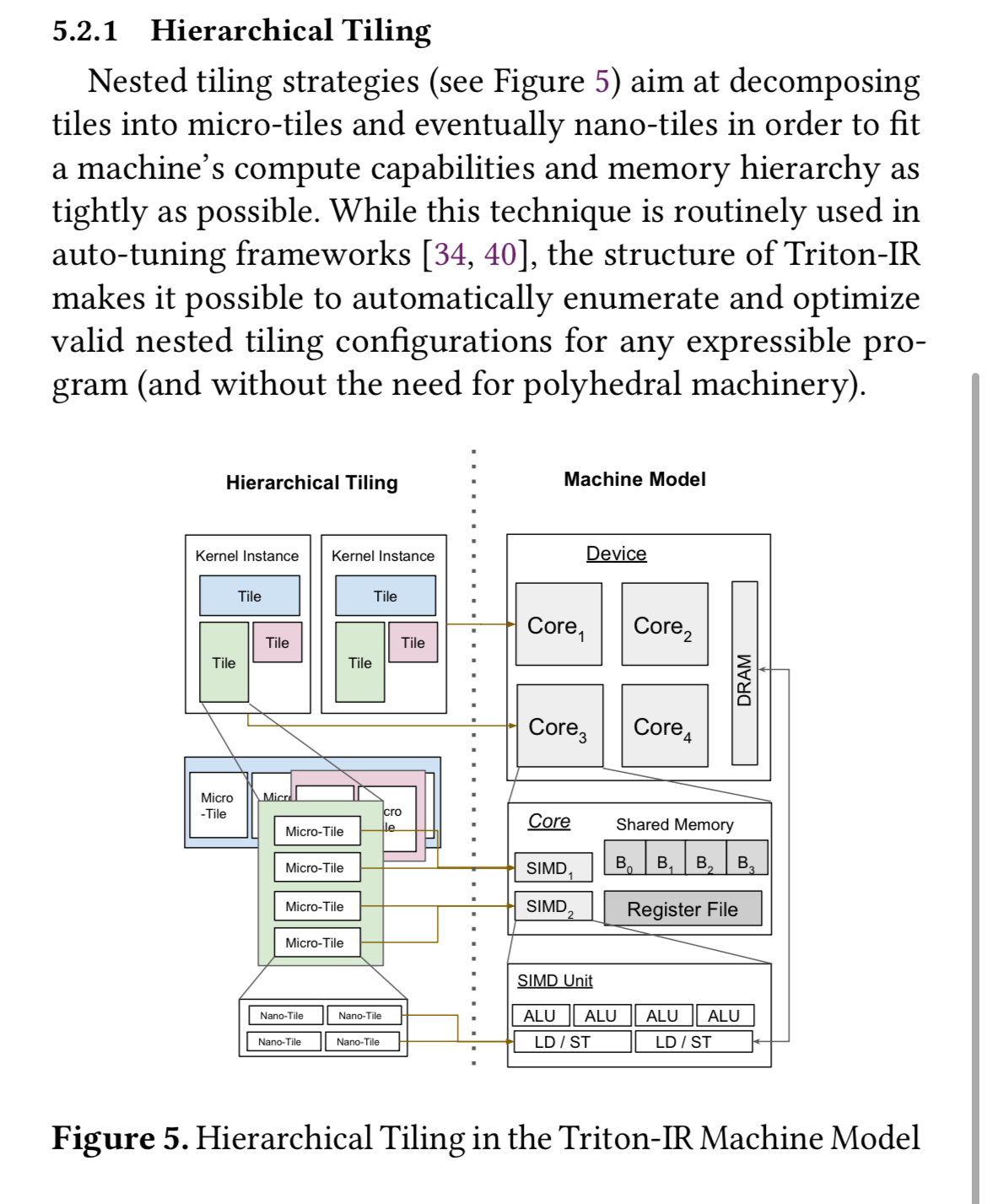

Beyond this, I dream about the potential of "cross-scheduler" systems optimization (i.e. Cubed vs the ML compiler). For example, in the accelerator literature, a lot of research effort has been invested in optimizing the memory layouts of data placed into accelerator memory. It turns out that if you "defrag" the memory layout, i.e. it is contiguous, it provides an affordance for you to hand-write GPU kernels to process arrays much more efficiently. This, in my understanding, underlies the Triton compiler from Harvard and OpenAI.

The task of this hand-tuning is known as "kernel lowering." Affordances for lowering have been made available in both PyTorch via Triton as well as Jax via Pallas. In my opinion, optimizations like these are incredibly worth it from an accelerator utilization perspective, but seldom invested in due to classic iteration cycles of ML modeling.

Imagine, if you will, being able to use memory-layout-optimized, kernel-lowered accelerated array operations, without having to spend days and days debugging every layer of the stack? This is the kind of "dual-scheduler" optimization that I hope is possible with Cubed.

At the core of both accelerator kernels and managing Zarr datasets is the abstraction of the "chunk." (I think the ML compiler literature might call them "tiles," but they buffer all the same.) What if Cubed could seamlessly manage memory at every level, from Zarr chunks to systolic array tiles? Are Zarr chunks not merely macro tiles?

This vision for Cubed may never be tractable. But, to me, it's something worth fighting for – one patch at a time. It's worthwhile to ground my dreaming in terms of practical milestones. I find these help me resolve ambiguities, such as what to develop now vs what to put off for later. In that spirit, I have a demo in mind to build around:

I want to perform an FFT on a Petabyte dataset, like ARCO-ERA5. And, I want to see if I can make it run substantially faster on accelerated hardware.

If everything goes right, I think the final code for the whole demo would look like this:

import xarray

import xrft

from cubed import Spec

from cubed.runtime.executors.lithops import LithopsDagExecutor

# TODO(alxmrs): how do you define a GPU-enabled spec?

spec = Spec(work_dir='tmp', allowed_mem='4GB')

ds = xarray.open_zarr(

'gs://gcp-public-data-arco-era5/ar/full_37-1h-0p25deg-chunk-1.zarr-v3',

chunks=None,

chunked_array_type='cubed',

from_array_kwargs={'spec': spec},

storage_options=dict(token='anon'),

)

ar_full_37_1h = ds.sel(time=slice(ds.attrs['valid_time_start'], ds.attrs['valid_time_stop']))

da = ar_full_37_1h['2m_temperature']

Fda = xrft.dft(da.isel(time=0), dim='lat', true_phase=True, true_amplitude=True)

Fda_1 = xrft.idft(Fda, dim='freq_lat', true_phase=True, true_amplitude=True, lag=45)

Fda_1.compute(executor=LithopsDagExecutor())Above code is based on examples from ARCO-ERA5, the xrft package, and Cubed-Xarray. Maybe FFTs will be supported in Cubed one day, who knows!

No, I am not sure. Ok, I think you're right. Single variables in ARCO-ERA5 are more like 4 TBs. This is where my lack of atmospheric-physics is showing – I'm not sure how to come up with a code example for computing an FFT in Xarray that would be at the petabyte scale. However, I suspect it would be quite possible to make one up. Maybe, it would look similar processing the model-view data, which is stored in a reduced gaussian grid.

This challenge is very inspired by this discussion in the Jax project inquiring how to perform FFTs of >100GB arrays. As of publication, it is currently unsolved. To me, performing FFTs on large datasets is a sort of "word-count" of array-processing frameworks: It's a simple enough problem that once achieved, proves capability of a huge class of problems.

In the future, my hope for Cubed is to become a new type of ML framework, maybe like Anyscale's Ray. With Cubed, I hope that ML developers never have to worry about OOM errors again (why not dream big? Though, there are lots of design opportunities to make this possible).

Thanks for reading to the end. If this topic interests you, please reach out to me (or file an issue in Cubed and tag me).